Research and Case Study 2: Phenomenology and the Body in Art and Design

- mrtnebusiness

- Sep 1

- 3 min read

When discussions about art or architecture turn to experience, they often emphasise what we see. Phenomenology insists instead that perception is embodied. We live through our bodies. We move, breathe, sense, remember and orient ourselves in space. This embodied approach has reshaped how we understand interior environments, sensory design and the emotional undercurrents of negative affect.

Phenomenology and Perception

Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception redefined perception as lived, embodied and always tied to the body’s presence in space (Merleau-Ponty, 1945). We do not view the world from outside. We inhabit it through a body that touches, senses and responds.

Juhani Pallasmaa applied this thinking to architecture, critiquing modern design’s reliance on vision alone. He argues that architecture should engage all senses: touch, sound, smell and memory bec,use the body is multidimensional (Pallasmaa, 2012). Peter Zumthor adds that good architecture is not simply built form but an atmosphere that lingers in the body (Zumthor, 2006).

The Multisensory Imagination

Elizabeth Grosz (2001) argues that the body is not passive matter but a threshold for experiencing space. Orientation, weight, gesture and movement structure how we perceive. Arnold Berleant (2010) develops this further through his aesthetics of engagement, where art and design are participatory, pulling us into their sensory field rather than holding us at a distance.

This is especially important when atmospheres provoke negative feelings. A space can make us anxious or unsettled by manipulating light, texture, acoustics and movement. The question is not just what we see but how the body feels when immersed in the environment.

Case Study 1: Olafur Eliasson, Your Blind Passenger (2010, Tate Modern)

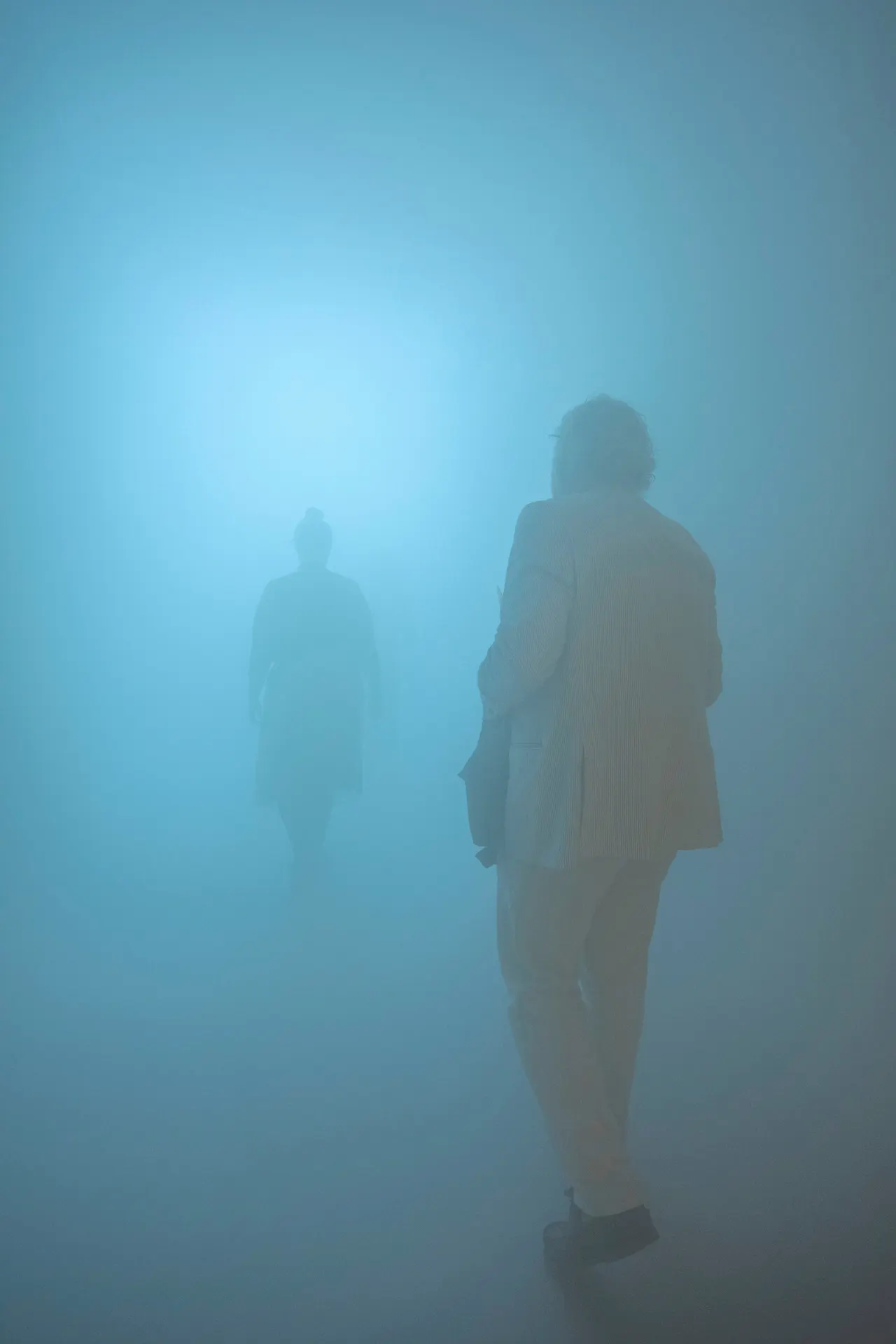

Olafur Eliasson’s Your Blind Passenger offered visitors a 45-metre interior corridor filled with dense artificial fog. Lit by shifting coloured light, the mist reduced visibility to little more than an arm’s length. As visitors moved forward, they had to rely on bodily orientation, cautious steps and trust in others moving alongside them.

The effect was both playful and disquieting. Many participants reported unease, a feeling of being lost or destabilised. The corridor transformed a simple walk into an anxious negotiation with the senses. In phenomenological terms, the work forced a return to the body: sight became unreliable, so touch, balance and proprioception took precedence. Eliasson demonstrated how interiors can stage atmospheres of both wonder and vulnerability through sensory disorientation.

Case Study 2: Doris Salcedo, Palimpsest (2017, Palacio de Cristal, Madrid)

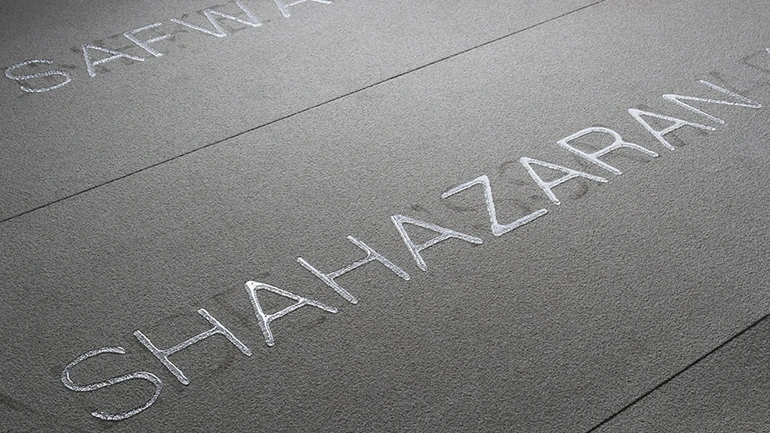

Doris Salcedo’s Palimpsest transformed the glass palace in Madrid into an atmosphere of mourning. The floor was inscribed with the names of migrants who had drowned while crossing seas to reach Europe. These names appeared through droplets of water seeping up through the stone, fading and reappearing in cycles.

The installation was visually subtle yet emotionally overwhelming. Visitors walked across the floor with care, aware that each step carried the weight of remembrance. The sound of water, the fragility of the inscriptions and the vast emptiness of the palace combined to create a space of unease and reflection. Phenomenologically, the work engaged sight, sound, touch and orientation, enveloping visitors in an atmosphere of loss. The interior was not neutral but saturated with grief and discomfort, embodied through material and sensory means.

Critical Reflections

These case studies show how phenomenological approaches to art and design translate into real practice. Both Eliasson and Salcedo foreground the body as the site of meaning. They produce atmospheres that cannot be reduced to visual form alone.

Yet they also highlight critical tensions. To what extent should art deliberately provoke negative feelings such as anxiety or grief ? Some critics suggest that inducing discomfort risks exploitation or spectacle. Others argue that these atmospheres are necessary to make hidden social realities perceptible. What is clear is that phenomenology provides a framework to evaluate how these works operate, grounding their effects in embodied experience rather than abstract theory.

Conclusion

Phenomenology reminds us that art and design are not detached spectacles but embodied events. The examples of Eliasson’s fog corridor and Salcedo’s watery inscriptions demonstrate that interiors can stage atmospheres of disorientation, unease and mourning through sensory means. They prove that the most powerful works are those that engage the body as much as the eye, inviting us to feel space rather than simply observe it.

References

Ahmed, S. (2006) Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Berleant, A. (2010) Sensibility and Sense: The Aesthetic Transformation of the Human World. Exeter: Imprint Academic.

Eliasson, O. (2010) Your Blind Passenger. Tate Modern, London.

Grosz, E. (2001) Architecture from the Outside: Essays on Virtual and Real Space. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945) Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by D.A. Landes. London: Routledge.

Pallasmaa, J. (2012) The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. 3rd edn. Chichester: Wiley.

Salcedo, D. (2017) Palimpsest. Palacio de Cristal, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid.

Zumthor, P. (2006) Atmospheres: Architectural Environments, Surrounding Objects. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Comments